Dublin High's 1963 State Football Championship

The Green and White returned to the Shamrock Bowl for the third game of the season against the previously undefeated Swainsboro Tigers, who outweighed the Greenies by thirty pounds per man. Nearly six thousand screaming fans showed up to see if the Irish could remain unbeaten. The Irish scored on their first drive and not again until their last three drives of the game to defeat the Swainsboro eleven 27 to 0. Chuck Frost became the first Irish running back to have a 100 yard rushing game, sixty-six of those yards coming on a touchdown run. The game was close until the Irish broke it open in the final stanza with three touchdowns by Danny Stanley (Left) , Robbie Hahn, and Chuck Frost. For the third straight game, the Irish held their opponents to less than 200 yards in total offense.

The Irish traveled to Cordele to defeat the Crisp County Rebels 34-0 to extend their winning streak to four games. The Irish scored on their opening drive with a 61-yard pass from Perry (Left) to Frost. The first half ended with Perry's 39-yard screen pass to Danny Stanley for a touchdown. Robbie Hahn, who went on to become a record breaking All American receiver for the Furman Palladins, scored on a long pass play. The star of the night was the fourteen-year-old sophomore Vic Belote, who scored on runs of 70 and 90 yards on his only carries of the night. The Banshees stymied the Rebels, holding them to only 97 yards of offense.

Camera and smiles flashed as the Panthers of Perry came to the Shamrock Bowl for the Homecoming Game. Linda Hobbs was crowned the Queen of Homecoming. Despite having an off night in losing four fumbles, the Irish pommeled the Panthers 41 -19. The Panthers managed to score 13 of their points in one 47 second span in the 4th quarter, an electrifying period in which the Irish scored their final 8 points in between. The Irish offense was led by Tom Perry's three touchdown passes to Chuck Frost (Left) , one long TD pass to Hahn, and two runs of 6 and 54 yards by Belote. Belote ran for 139 yards to led the Irish running backs. The Banshees held the Perry team to 143 yards of offense, and keeping them from passing the line of scrimmage on thirteen running plays.

The 9th game of the season came in Americus. It wasn't pretty. The Irish played horribly. The Americus Panthers, well, they were just too much for the boys in green. Chuck Frost and Tom Perry were knocked out of the game on the same play when they tackled an Americus runner. The score, an old fashioned butt whooping 35-7 loss to the defending state champions.

After an intensive 11-week season fifty years ago in 1963, the Dublin Irish took time to pause for the state playoffs. In those days, there were only four regions in Class A and only four participants in the state tournament, unlike the 32-team tournament format of today. The Irish had the first week off while the three top teams in Region 1 fought it out to determine who would meet the Banshees in the South Georgia Championship game. Thomasville trounced Americus, a team which dominated Dublin in their only loss, by the score of 26-0. Then the Bulldogs defeated region rival Cook County by practically the same score.

From the beginning, controversy engulfed the game. Thomasville officials refused to allow a Dublin radio station to broadcast the game by telephone back home to Dublin. Dublin boosters were only allotted 192 reserved seats along the fifty yard line. The seats that were there were only on one side of the field, so Dublin and Thomasville fans shared the same side of the field. Those who couldn't find a seat, stood on the opposite side of the field while the cold winds of November howled through the stadium in Thomasville.

The ball game was a close as the Thomasville and Dublin fans were crammed into the seats. Neither team penetrated the other's goal line during the first half. In the third quarter, the Irish mounted their only scoring drive of the game. Stanley ran the ball for two. Belote fumbled and Perry recovered for a 4-yard loss. Perry then tossed a 23 yard pass to Hahn. Stanley was held to 1 yard gain on first down. Perry turned back to the speedy Hahn for 16. The Bulldogs caught Stanley in the backfield for a 2-yard loss and a 1-yard gain. On third and long, Perry hooked up with Hahn for his third catch of the drive on a 14-yard pass. Stanley then took matters into his own hands. He wouldn't be denied. He gathered in a screen pass and blasted his way for 12 yards. He took the next handoff at the 13-yard line and ran it to the 4. Running behind Marion Mallette and Charles Faulk, (Left) Stanley drove it down to the two. Quarterback Perry huddled the team and called "same play." Stanley squeezed the ball and dove into the Thomasville end zone to consummate a twelve-play eighty-yard drive to put the Irish ahead. Tom Perry's kick after touchdown struck the right goal post and bounced haplessly away.

Coach Minton Williams cited the great job of blocking and defense as the reason for the Dublin win. Larry Jones (Left) stopped a critical Bulldog drive with a fumble recovery. Another defensive star was Chuck Frost, who had to leave the game early when he broke his finger in stopping a sure Thomasville touchdown. Johnny Malone saved his best game of the season for South Georgia championship.

The championship game was set at the 8000 seat North Dekalb Stadium. Again all the seats were on the same side of the field. This time however, the Irish were on the opposite sidelines, all by themselves. The opposition was Tucker High School, who were playing in their own territory. Coach Williams expected that the boys from Tucker would concentrate on pass defense, so he ran the ball and he ran the ball. With Senior Danny Stanley and Sophomore Vic Belote running the ball behind the powerful offensive line, the Galloping Green dominated the line of scrimmage. Three long Dublin drives ended with two fumbles inside the Tucker 10-yard line and an interception at the opposition's 3-yard line.

Taking the ball at their own 3-yard line following a Thomasville punt, the Irish moved 89 yards on runs totaling 50 yards by Stanley, 25 yards by Belote, and 14 by Chuck Frost. With the Irish leading 7-6 and the ball at the Tucker 5-yard line, Stanley took the ball on a 4th down and 1 yard play into the end zone to give Dublin a 13-6 lead after the extra point attempt sailed wide to the left. Tucker roared back with a touchdown which brought the score perilously close at 13-12. Tucker lined up for a two-point conversion and the lead.

The game was a close as you could get. The Dublin one point victory was matched by a 2-yard edge in rushing (263-261), a 1-yard margin in passing (54-53), and a 1-first down deficit (12-13). Each team completed only three passes. The crowd swarmed the field as the Irish had captured their 3rd State Championship in five years, ending their tenure in Class A as Kings of Georgia football.

While the Atlanta Constitution ignored Minton Williams as its coach of the year in favor of the losing coach from Tucker, the Irish placed four members on the all state team. Quarterback Tom Perry, half back Danny Stanley, and end Robbie Hahn joined Charles Faulk, a repeater from the 1962 team at tackle. So ended the last championship season for forty three years.

They called them the Banshees. They were small. They were fast. They were stingy on defense. The Dublin Irish football team had won Class A championships and 1959 and 1960, but had succumbed to the more powerful Sylvania Gamecocks in the following two seasons. The 1963 edition of the Dublin Irish sported a new look and a new enthusiasm. It was the last time Dublin would win a state football championship. There were other times when we came close. There was a loss to Carver High School in a mud bowl in 1967. The 1994 team was defeated by Thomasville, one of the top-ranked teams in the country. Most recently, there was the hard-fought heart-breaking loss to Screven County, which ended the Cinderella season of one of Dublin High's greatest all time teams. This is the story of a group of small boys, who played hurt, fought hard, and climbed their way back to the pinnacle of Class A Georgia football, a half century ago.

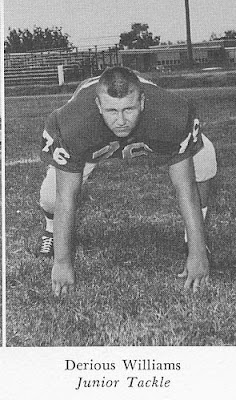

The new look Irish with seventeen seniors sported a new look, dark green uniforms with white numbers. They were considerably smaller than past Irish teams. The offensive line averaged 169 pounds. Marion Mallette was the biggest offensive lineman tipping the scales at 205 pounds, while Chub Forth was a speedy 145-pound guard. Tom Perry, the quarterback, was the largest back at 170 pounds. The defensive line weighed in at 175 pounds, with Derious Williams the big man at 215 and the nose guard Bob Mathis anchoring the line at an unheard of weight of 140 pounds.

The Irish opened the 1963 season in the Shamrock Bowl in front of a crowd of 4000, the largest in the stadium's young history. Steve Walker and Ronnie Williams led the award winning Dixie Irish Band. Sharon Lamb captained the cheerleading squad. The Irish, running a new pro-style offense, were led by Quarterback Tom Perry, who passed for two touchdowns and ran for one more. Vic Belote was cited for his great play on both sides of the line of scrimmage in a 20-6 victory over the Dodge County Indians. The vaunted Banshee defense, led by an interception by Joel Smith and a fumble recovery by Charles Faulk, kept the red men in check by holding them to 126 yards of total offense. The boys from Dodge County managed their lone score late in the game.

The Irish traveled to Fort Valley the following week to face the Green Wave. Sophomore running back Vic Belote, (Left) subbing for the injured Danny Stanley, ran for 80 yards. The Galloping Green offense scored on three long drives culminating in a run by Belote, and receptions by Frost and Hahn. Robbie Hahn began the season as the place kicker and punter. The Irish defense shut out the Green Wave 20 to 0, allowing 134 yards of offense.

The Green and White returned to the Shamrock Bowl for the third game of the season against the previously undefeated Swainsboro Tigers, who outweighed the Greenies by thirty pounds per man. Nearly six thousand screaming fans showed up to see if the Irish could remain unbeaten. The Irish scored on their first drive and not again until their last three drives of the game to defeat the Swainsboro eleven 27 to 0. Chuck Frost became the first Irish running back to have a 100 yard rushing game, sixty-six of those yards coming on a touchdown run. The game was close until the Irish broke it open in the final stanza with three touchdowns by Danny Stanley (Left) , Robbie Hahn, and Chuck Frost. For the third straight game, the Irish held their opponents to less than 200 yards in total offense.

The Irish traveled to Cordele to defeat the Crisp County Rebels 34-0 to extend their winning streak to four games. The Irish scored on their opening drive with a 61-yard pass from Perry (Left) to Frost. The first half ended with Perry's 39-yard screen pass to Danny Stanley for a touchdown. Robbie Hahn, who went on to become a record breaking All American receiver for the Furman Palladins, scored on a long pass play. The star of the night was the fourteen-year-old sophomore Vic Belote, who scored on runs of 70 and 90 yards on his only carries of the night. The Banshees stymied the Rebels, holding them to only 97 yards of offense.

The Washington County Golden Hawks were the opponents to end the first half of the regular season. The Galloping Green put up 387 yards of offense with scores by Stanley, Hahn, Frost, Blue, and Powell. (Left) The Irish got off to a slow start, but won the game 38-6. Joel Smith snatched his second errant Golden Hawk pass of the game and raced 25 yards into the end zone for a rare defensive touchdown. The boys from Sandersville were held to 111 yards of offense.

Camera and smiles flashed as the Panthers of Perry came to the Shamrock Bowl for the Homecoming Game. Linda Hobbs was crowned the Queen of Homecoming. Despite having an off night in losing four fumbles, the Irish pommeled the Panthers 41 -19. The Panthers managed to score 13 of their points in one 47 second span in the 4th quarter, an electrifying period in which the Irish scored their final 8 points in between. The Irish offense was led by Tom Perry's three touchdown passes to Chuck Frost (Left) , one long TD pass to Hahn, and two runs of 6 and 54 yards by Belote. Belote ran for 139 yards to led the Irish running backs. The Banshees held the Perry team to 143 yards of offense, and keeping them from passing the line of scrimmage on thirteen running plays.

In the closest game of the regular season, the Dublin boys defeated the Braves of Baldwin County 21 to 14 in Milledgeville. It was Danny Stanley's greatest game of his career in a Dublin uniform. Stanley carried the ball 27 times for 141 yards, out rushing the entire Baldwin County running back corps. The Irish came from behind for the first time with two touchdown runs by Stanley and a pass from Perry to Hahn. (Left) The Irish were plagued with a series of mental lapses and miscues, which nearly ended their six game winning streak. The Irish ground game was stymied when Vic Belote left the game with a badly bruised hand. For the seventh straight game, the Irish defense held their opponents to less than 200 yards of total offense.

A win over Statesboro in the Shamrock Bowl would clinch the 2A Title for the Irish. A cold rain kept the crowd down to the smallest it had been since the bowl opened for play in 1962. Louie Blue scored his first touchdown of the season, while regular scorers Belote and Hahn picked up one score apiece. Two Irish touchdowns were called back, holding the score to a 19-0 Dublin victory. Robbie Hahn boomed a 63-yard punt to end the first half. The Irish defense aided by wet pigskins held the Blue Devils to 66 yards of total offense, all on the ground.

Dublin faced their region nemesis Screven County in the final game of the regular season. The Irish managed a 26-6 victory over the Gamecocks, who had dominated the region for the past two seasons, but failed to gain a single passing yard. A encouraging highlight of the future of Irish football came when Stanley Johnson, an eighth grade runner with electrifying speed, dashed 14 yards into the end zone. By the end of the season, the Irish were playing hurt. Chuck Frost substituted at quarterback for Perry, who had broken his thumb in practice and bruised his ribs in the loss to Americus. Center Bernard Snellgrove (Left) stood on the side lines on a bum leg. Vic Belote sucked it up and played the entire game both ways while suffering from a broken thumb.

After an intensive 11-week season fifty years ago in 1963, the Dublin Irish took time to pause for the state playoffs. In those days, there were only four regions in Class A and only four participants in the state tournament, unlike the 32-team tournament format of today. The Irish had the first week off while the three top teams in Region 1 fought it out to determine who would meet the Banshees in the South Georgia Championship game. Thomasville trounced Americus, a team which dominated Dublin in their only loss, by the score of 26-0. Then the Bulldogs defeated region rival Cook County by practically the same score.

Almost a week before the first game, the players and the nation were stunned by the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas. The players and coaches attended a memorial service at First Methodist Church before resuming their practice schedule.

The ball game was a close as the Thomasville and Dublin fans were crammed into the seats. Neither team penetrated the other's goal line during the first half. In the third quarter, the Irish mounted their only scoring drive of the game. Stanley ran the ball for two. Belote fumbled and Perry recovered for a 4-yard loss. Perry then tossed a 23 yard pass to Hahn. Stanley was held to 1 yard gain on first down. Perry turned back to the speedy Hahn for 16. The Bulldogs caught Stanley in the backfield for a 2-yard loss and a 1-yard gain. On third and long, Perry hooked up with Hahn for his third catch of the drive on a 14-yard pass. Stanley then took matters into his own hands. He wouldn't be denied. He gathered in a screen pass and blasted his way for 12 yards. He took the next handoff at the 13-yard line and ran it to the 4. Running behind Marion Mallette and Charles Faulk, (Left) Stanley drove it down to the two. Quarterback Perry huddled the team and called "same play." Stanley squeezed the ball and dove into the Thomasville end zone to consummate a twelve-play eighty-yard drive to put the Irish ahead. Tom Perry's kick after touchdown struck the right goal post and bounced haplessly away.

It was then up to the vaunted Banshee defense to hold the heavily favored Bulldog offense.

The Thomasville boys struck back with a one-play forty-five yard drive on run by all-state running back Dickie Thompson to tie the score at 6-6. The snapper snapped. The holder tried to upright the pigskin for the kick. It was all to no avail. As the kicker kicked the horizontal ball, the Banshees swarmed all over it like ducks on a June bug. The clock ran out with the score standing at a "sister-kissing" tie, 6-6. In 1963, there was no overtime. The winner of the game would be determined by giving one point to the team leading in three categories: most offensive yards, most first downs, and most penetration inside the opponent's 20 yard line. By virtue of their lead in all three categories, the Irish were awarded three points and won the game 9-6.

Coach Minton Williams cited the great job of blocking and defense as the reason for the Dublin win. Larry Jones (Left) stopped a critical Bulldog drive with a fumble recovery. Another defensive star was Chuck Frost, who had to leave the game early when he broke his finger in stopping a sure Thomasville touchdown. Johnny Malone saved his best game of the season for South Georgia championship.

The championship game was set at the 8000 seat North Dekalb Stadium. Again all the seats were on the same side of the field. This time however, the Irish were on the opposite sidelines, all by themselves. The opposition was Tucker High School, who were playing in their own territory. Coach Williams expected that the boys from Tucker would concentrate on pass defense, so he ran the ball and he ran the ball. With Senior Danny Stanley and Sophomore Vic Belote running the ball behind the powerful offensive line, the Galloping Green dominated the line of scrimmage. Three long Dublin drives ended with two fumbles inside the Tucker 10-yard line and an interception at the opposition's 3-yard line.

The Irish began their first scoring drive at their own 23. Perry tossed a 22 yard pass to Hahn. He came back with another pass, this one a 29-yard spectacular catch by Hahn with 27 seconds left in the first half. From nearly the same position on the field that Irish had against Thomasville the week before, Coach Williams, with 14 seconds left called for a screen pass, which Stanley again grabbed and jaunted down to the Tucker 1 yard line. With the clock standing at four seconds, Stanley ran behind a powerful block of Jack Stafford (Left) for a 1-yard dive play. Hahn kicked the extra point to give the Irish the lead with no time left to play.

Following a quick score by Tucker, the Irish exhibited a strong ground game to grind out the clock.

Taking the ball at their own 3-yard line following a Thomasville punt, the Irish moved 89 yards on runs totaling 50 yards by Stanley, 25 yards by Belote, and 14 by Chuck Frost. With the Irish leading 7-6 and the ball at the Tucker 5-yard line, Stanley took the ball on a 4th down and 1 yard play into the end zone to give Dublin a 13-6 lead after the extra point attempt sailed wide to the left. Tucker roared back with a touchdown which brought the score perilously close at 13-12. Tucker lined up for a two-point conversion and the lead.

That is when the controversy, at least on the part of the Tucker fans and the Atlanta newspaper reporter began. The quarterback faked a dive play into the line. Defensive lineman Larry Jones, well coached on the art of goal line defense, dove at the offensive end's feet just as he was supposed to do and took him out. It just happened that the end was the one the quarterback had called to catch the pass. The front seven Banshees focused in on getting to the ball. The Tucker quarterback, with his primary receiver lying on the cold tundra, heaved the ball into the end zone praying for a miracle. The miracle never came. The ball landed beyond the grasps of any player.

Charles Roberts of the Atlanta Constitution accused the referees of ignoring a flagrant hold by Jones on the play. The Irish coaches responded to the baseless charges by stating that "our player was doing what he supposed to do."

The Irish tried to put an insurance touchdown on the board but were stopped at the Tucker 22-yard line with a long penalty. Then the Banshee defense made one last stand and stopped a Tucker drive, much to the sheer delight of the 2500 Dublin fans who had traveled to the game. The game ended with the score, Dublin 13, Tucker 12.

The game was a close as you could get. The Dublin one point victory was matched by a 2-yard edge in rushing (263-261), a 1-yard margin in passing (54-53), and a 1-first down deficit (12-13). Each team completed only three passes. The crowd swarmed the field as the Irish had captured their 3rd State Championship in five years, ending their tenure in Class A as Kings of Georgia football.

The Dublin Irish ended the season with a record of 11 and 1. They outscored their opponents by an average of 23 to 8 during the season. The stingy Irish defense held their opponents to an average of less than 50 yards a game in passing defense. The Banshees shut out their opponents four times and held them to six points in three games.

The primary members of the 1963 Class A State Football Champions were: Vic Belote, Louie Blue, Don Bracewell, Ronald Cook, Otha Dixon, Ben Eubanks, Charles Faulk, Jimmy Fort, Chub Forth, Chuck Frost, Robbie Hahn, Charlie Harpe, Stanley Johnson, Larry Jones, Marion Mallette, Johnny Malone, Danny Misseri, Tom Perry, Johnny Phelps, Alan Powell, Dwyane Rowland, Joel Smith, Bernard Snellgrove, Earl Snipes, Jack Stafford, Danny Stanley, Ben Stephens, Edwin Wheeler, Derious Williams, Brooks Wright, and Freeman Young. Coaches: Minton Williams, Travis Davis, Bob Morrow and George Sapp. Trainer/Sr. Manager: Johnny Warren, Managers: Mike Daily and Jerry Spivey.

_4.jpg)