IT'S SO, SHOELESS JOE PLAYED HERE

Banned from the sport he loved so dearly, Joseph Jefferson Jackson toured the South playing for the love of the game and the bounties of the baseball promoters. Thousands of adoring fans surrounded sandy diamonds throughout the Southeast eager to catch a glimpse of the man they called "Shoeless Joe." Back in 1925, this unjust exile played two games in Dublin, never losing a step from the decade of the 1910s, when Joe Jackson was one of baseball's greatest players.

Joe Jackson was born in South Carolina in 1887. At the age of six, he began to work in the textile mills, which were a dominant part of his community's economy. Upon his becoming a teenager, Joe was asked to join the mill's baseball team. Since he worked half of every day in the mill, with an occasional break to play ball, Joe never obtained any degree of education, a misfortune which would haunt him for the rest of his life. On Saturdays he would pick up a few dollars by playing baseball. By the time he was twenty, Joe signed to play semi-pro ball with the Greenville Spinners for a lucrative $75.00 per month. By the end of August, he made it to the major leagues, but disappointedly, Joe only played in five games. Jackson returned to the minor leagues, only to return to the big leagues in 1910 as a member of the Cleveland Indians of the American League.

As a rookie in 1911, Joe batted .408, the first and only rookie ever to exceed the highly coveted level of batting supremacy. His batting average dipped to .395 in 1912, but the twenty-five-year-old phenom led the league in triples. The following year Jackson led the league in hits and slugging average. In 1915, Jackson was traded to the White Sox for cash and three players. For the next five seasons, Joe Jackson was a terror in the batter's box, never falling below .300.

Joe Jackson's colorful nickname was reportedly penned on him during a mill league game against a team from Anderson, South Carolina. Joe supposedly discarded a new pair of spikes when they began to rub blisters on his feet. He played the rest of the game in his stocking feet. During his first plate appearance without shoes, Joe stroked a triple deep into the outfield, prompting an opposing fan to shout, "You shoeless son of gun, you!"

The zenith of Joe's career came in 1919 when his team, the Chicago White Sox, faced the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series. The Sox lost the best of nine series, five games to three. During the series, Joe was the only player to hit a home run and played outstanding ball in the field and at the plate. Joe continued to excel in 1920, posting a .385 average and leading the league in triples for the third time. Joe and seven other White Sox players, an octette dubbed the "Black Sox," were implicated in a scandal which accused Joe and his teammates of throwing the series. Joe and the others were suspended from baseball until their fate could be determined.

In 1921, Joe Jackson was acquitted of any malfeasance in the series by a Chicago jury. Despite his exoneration, he was banned from baseball for life by Kennesaw Mountain Landis, baseball's first commissioner, for his failure to disclose his knowledge of the conspiracy. He returned home to Savannah, where he opened a lucrative dry-cleaning business. But as soon as the temperatures of the spring began to rise, offers for his services on semi-pro teams throughout the South and the North came pouring in. In the summer of 1923, Joe began the season playing in Bastrop, Louisiana. Near the middle of the season, Joe accepted an offer by a team from Americus, Georgia. He led the team to the championship of the South Georgia League, batting .453 in 25 games and .500 in the league championship series over Albany. He even pitched one inning, surrendering one base on balls, but no hits or runs. After the end of the South Georgia League season, Joe played with the railroad team out of Waycross, Georgia. In 1924, Jackson led the Waycross Coast Liners to the Georgia Championship, doubling as the team's manager during the last half of the season.

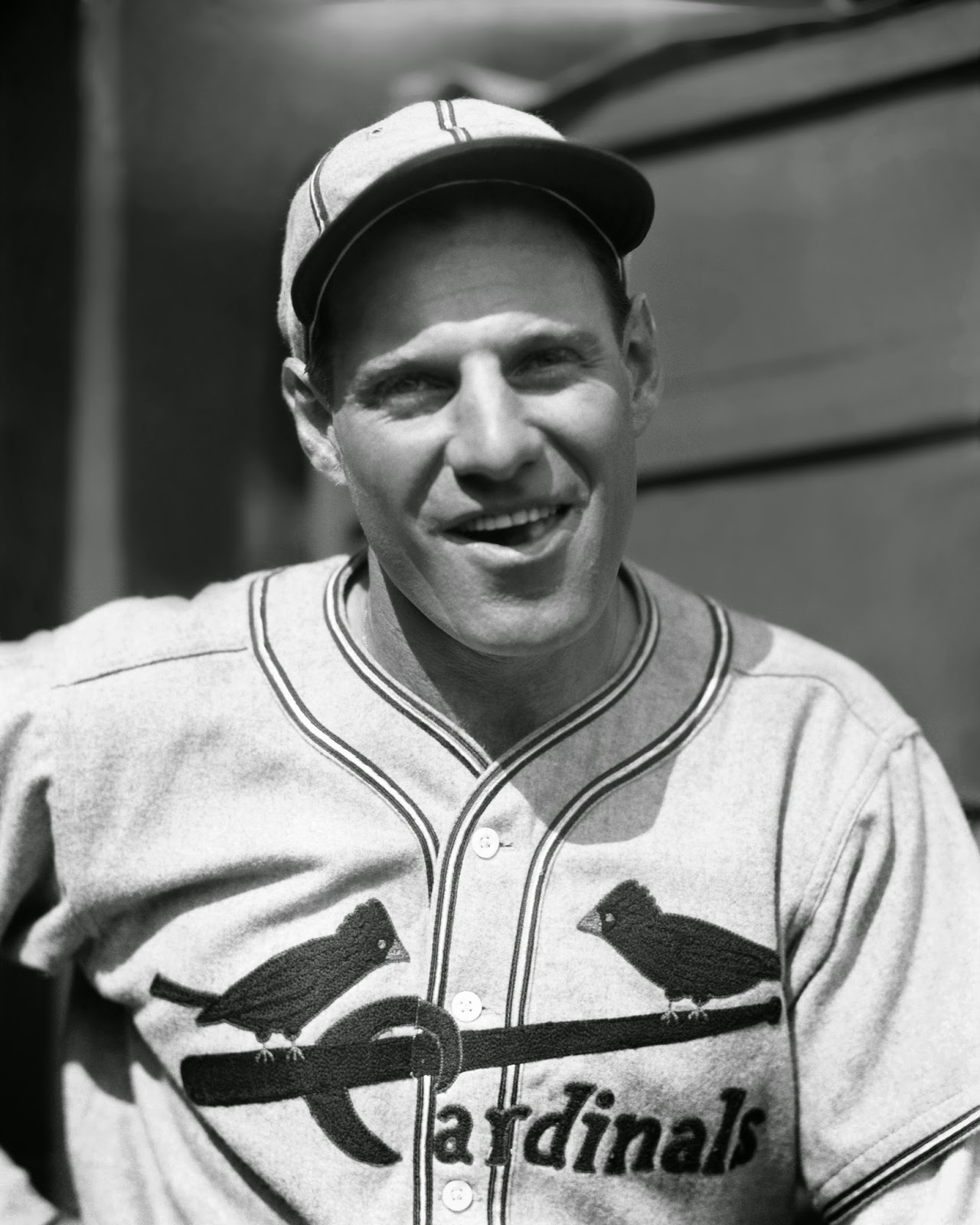

In his last full professional season with Waycross in 1925, Joe played center field and managed the Coast Liners to an impressive record of 63-19-3. The Waycross team played teams from Georgia, as well as ones from Florida, Alabama and South Carolina. On June 22, 1925, the Coast Liners played the Right of Ways from Macon, Georgia, a team fielded by the Central of Georgia Railroad, on the 12th District Fairgrounds in Dublin. The ball field, located at the western corner of Telfair and Troup streets, was the scene of a 1918 game between the New York Yankees and the Boston Braves and games between Oglethorpe University and the University of Georgia and the St. Louis "Gas House Gang" Cardinals in 1933 and 1935.

Regretfully, only sketchy details of the game have survived. Joe's team won the first game, 8-7 on a field described as "rough and in very bad condition." While no box score was published in the Macon Telegraph, Jackson was credited with leading his team to victory. After the game, the field was improved for the next day's game, in which the Macon boys won by the score of 11-7. A third game was apparently canceled, and the teams played two more games in Macon the following weekend.

One of "Shoeless Joe's" teammates on the 1925 Coast Liner team was William C. Webb. Webb was born in Adrian, Georgia in 1903. He graduated from Adrian High School and played college ball at Sparks Junior College. Webb played under Jackson, whom he described as "a good baseball man." In a 2001 interview with John Bell, author of "Shoeless Summer" and "Georgia Class D Minor League Encyclopedia," Webb said of Jackson "Even though he was not educated, he had the ability to make managerial decisions that almost always turned out well. He was a player's manager, who led by example and had great respect for his players." Webb admired Jackson, who once let the country boy bat with his famous bat "Black Betsy," a hand-fashioned stick of hickory with a slight bend and which sounded like he hit a brick when he struck the ball. Webb told his interviewer that he often had to help the uneducated superstar by assisting him in signing his name on the back of his paychecks. Webb went on to play semi-pro ball well into his thirties.

Joe continued to play some mill league and semi-pro ball until 1941, when he played his first and last night games at the age of fifty-four, belting two home runs in a single game, when most men his age have long given up hopes of playing the game of their youth. His statistics after 1925 are very scant. Joe often played under assumed names. Foster Taylor, the former beloved Mayor of Rentz, Georgia, always recalled the time that he played in a game with the great "Shoeless Joe." Joe Jackson operated a liquor store and barbecue restaurant in Greenville, South Carolina until his death at the age of 64 on December 5, 1951.

More than a half century after his death, sincere and enduring baseball fans and former players are still seeking to add the name of Joseph Jefferson Jackson to the Baseball Hall of Fame. After all is said and done, he was absolved of any wrong doing by a jury of his peers and was a player whose .356 lifetime batting average is the 3rd highest in baseball history. Maybe one day when the summer skies are brightly shining in Cooperstown, New York, the announcer will step up to the podium and announce the name of "Shoeless Joe" Jackson to his rightful place among the ultimate immortals of the country's national pastime.

Banned from the sport he loved so dearly, Joseph Jefferson Jackson toured the South playing for the love of the game and the bounties of the baseball promoters. Thousands of adoring fans surrounded sandy diamonds throughout the Southeast eager to catch a glimpse of the man they called "Shoeless Joe." Back in 1925, this unjust exile played two games in Dublin, never losing a step from the decade of the 1910s, when Joe Jackson was one of baseball's greatest players.

Joe Jackson was born in South Carolina in 1887. At the age of six, he began to work in the textile mills, which were a dominant part of his community's economy. Upon his becoming a teenager, Joe was asked to join the mill's baseball team. Since he worked half of every day in the mill, with an occasional break to play ball, Joe never obtained any degree of education, a misfortune which would haunt him for the rest of his life. On Saturdays he would pick up a few dollars by playing baseball. By the time he was twenty, Joe signed to play semi-pro ball with the Greenville Spinners for a lucrative $75.00 per month. By the end of August, he made it to the major leagues, but disappointedly, Joe only played in five games. Jackson returned to the minor leagues, only to return to the big leagues in 1910 as a member of the Cleveland Indians of the American League.

As a rookie in 1911, Joe batted .408, the first and only rookie ever to exceed the highly coveted level of batting supremacy. His batting average dipped to .395 in 1912, but the twenty-five-year-old phenom led the league in triples. The following year Jackson led the league in hits and slugging average. In 1915, Jackson was traded to the White Sox for cash and three players. For the next five seasons, Joe Jackson was a terror in the batter's box, never falling below .300.

Joe Jackson's colorful nickname was reportedly penned on him during a mill league game against a team from Anderson, South Carolina. Joe supposedly discarded a new pair of spikes when they began to rub blisters on his feet. He played the rest of the game in his stocking feet. During his first plate appearance without shoes, Joe stroked a triple deep into the outfield, prompting an opposing fan to shout, "You shoeless son of gun, you!"

The zenith of Joe's career came in 1919 when his team, the Chicago White Sox, faced the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series. The Sox lost the best of nine series, five games to three. During the series, Joe was the only player to hit a home run and played outstanding ball in the field and at the plate. Joe continued to excel in 1920, posting a .385 average and leading the league in triples for the third time. Joe and seven other White Sox players, an octette dubbed the "Black Sox," were implicated in a scandal which accused Joe and his teammates of throwing the series. Joe and the others were suspended from baseball until their fate could be determined.

In 1921, Joe Jackson was acquitted of any malfeasance in the series by a Chicago jury. Despite his exoneration, he was banned from baseball for life by Kennesaw Mountain Landis, baseball's first commissioner, for his failure to disclose his knowledge of the conspiracy. He returned home to Savannah, where he opened a lucrative dry-cleaning business. But as soon as the temperatures of the spring began to rise, offers for his services on semi-pro teams throughout the South and the North came pouring in. In the summer of 1923, Joe began the season playing in Bastrop, Louisiana. Near the middle of the season, Joe accepted an offer by a team from Americus, Georgia. He led the team to the championship of the South Georgia League, batting .453 in 25 games and .500 in the league championship series over Albany. He even pitched one inning, surrendering one base on balls, but no hits or runs. After the end of the South Georgia League season, Joe played with the railroad team out of Waycross, Georgia. In 1924, Jackson led the Waycross Coast Liners to the Georgia Championship, doubling as the team's manager during the last half of the season.

Regretfully, only sketchy details of the game have survived. Joe's team won the first game, 8-7 on a field described as "rough and in very bad condition." While no box score was published in the Macon Telegraph, Jackson was credited with leading his team to victory. After the game, the field was improved for the next day's game, in which the Macon boys won by the score of 11-7. A third game was apparently canceled, and the teams played two more games in Macon the following weekend.

One of "Shoeless Joe's" teammates on the 1925 Coast Liner team was William C. Webb. Webb was born in Adrian, Georgia in 1903. He graduated from Adrian High School and played college ball at Sparks Junior College. Webb played under Jackson, whom he described as "a good baseball man." In a 2001 interview with John Bell, author of "Shoeless Summer" and "Georgia Class D Minor League Encyclopedia," Webb said of Jackson "Even though he was not educated, he had the ability to make managerial decisions that almost always turned out well. He was a player's manager, who led by example and had great respect for his players." Webb admired Jackson, who once let the country boy bat with his famous bat "Black Betsy," a hand-fashioned stick of hickory with a slight bend and which sounded like he hit a brick when he struck the ball. Webb told his interviewer that he often had to help the uneducated superstar by assisting him in signing his name on the back of his paychecks. Webb went on to play semi-pro ball well into his thirties.

Joe continued to play some mill league and semi-pro ball until 1941, when he played his first and last night games at the age of fifty-four, belting two home runs in a single game, when most men his age have long given up hopes of playing the game of their youth. His statistics after 1925 are very scant. Joe often played under assumed names. Foster Taylor, the former beloved Mayor of Rentz, Georgia, always recalled the time that he played in a game with the great "Shoeless Joe." Joe Jackson operated a liquor store and barbecue restaurant in Greenville, South Carolina until his death at the age of 64 on December 5, 1951.

More than a half century after his death, sincere and enduring baseball fans and former players are still seeking to add the name of Joseph Jefferson Jackson to the Baseball Hall of Fame. After all is said and done, he was absolved of any wrong doing by a jury of his peers and was a player whose .356 lifetime batting average is the 3rd highest in baseball history. Maybe one day when the summer skies are brightly shining in Cooperstown, New York, the announcer will step up to the podium and announce the name of "Shoeless Joe" Jackson to his rightful place among the ultimate immortals of the country's national pastime.